1970 Exterior Photographs of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston

For 100 years, women accept embraced way that was once merely considered appropriate for men, like suits, military jackets, blue jeans, and brogues. Why hasn't it go the norm for men to have on traditionally feminine clothing? Will information technology ever be socially acceptable for more men to wear skirts and dresses?

These are some of the questions that Michelle Finamore asked as she curated theGender Bending Manner exhibit at Boston's Museum of Fine Arts. The exhibition is a psychedelic feel. The infinite is moody and dark, with light-green, xanthous, and reddish neon lights illuminating faceless mannequins, crafted by the MFA's in-house designer Chelsea Garunay. Finamore chose to accept an ahistorical approach to fashion: Outfits from different moments over the by century sit beside each other, with '90s men'due south kilts next to a women'southward bicycling ensemble from 1900. Interspersed among everyday looks are dress by designers that have played around with gender norms, including Christian Siriano, Yves Saint Laurent, Rick Owens, Rei Kawakubo for Commes Les Garcons, and Alessandro Michele for Gucci.

This allows the viewer to see the outfits out of their context–and better identify patterns. And it rapidly becomes clear that there are recurring motifs. The dark adjust, with its boxy shoulders and precipitous angles, comes to represent masculine dress. Meanwhile, colorful patterns and flowing robes embody the feminine. Merely these two forms of wearing apparel are slowly colliding in our current moment. The time to come of fashion appears to be neither masculine, nor feminine, just an intriguing hybrid of the two.

The Armor of Patriarchal Power

The dark business organization suit is a relatively recent miracle. Finamore, who studies clothing in the 20th and 21st century, believes that our civilisation has transformed the accommodate into a symbol of patriarchal power. Before the 19th century, European aristocratic men tended to clothing colorful, frilly outfits, along with wigs that gave the appearance of long hair. Simply then, in the early 1800s, wealthy men began wearing well-cut tailored suits in somber colors, similar black, gray, and blue. This is still true today, peculiarly in male-dominated industries like finance, consulting, and constabulary. The shift occurred during the period later on the industrial revolution, when middle-form women were increasingly relegated to the domicile, while men were out in public spaces working. "There was this idea that colors and patterns were frivolous, and something that women cared about," Finamore points out. "So these things came to exist characterized as feminine."

As I've written in the past, women have tried to access patriarchal power by wearing the suit, particularly in workplaces where women are in the minority. Startups like Argent and Dai specialize in creating suits for women. Even Savile Row, which emerged in the 19th century equally the get-to place for wealthy British men to take suits made, is now reinventing itself to cater to women.

While women have gladly taken on the iconic male garment of our time, men, for their part, have not been as audacious. In fact, men seem to be clinging onto the suit–and offshoots of it, similar the blazer and the chino–equally their standard form of dress. Not merely are these wearing apparel carefully designed to facilitate motility, they besides project power and authority toward others. "The concern suit has become so entrenched in Western civilization and now in non-Western cultures, likewise," says Finamore. "Men are loathe to give that upwardly."

How Women Got On Board With Male Clothes

Just fifty-fifty as men have stubbornly stuck to traditionally masculine clothing, women have been eager to adopt the clothes of their male counterparts. As the exhibit shows, women frequently adopted male garments considering they were more practical and allowed women to move more freely. For instance, women first gave up their skirts and petticoats considering they wanted to have function in outdoor activities, like bicycling or fox hunting past horseback. Under neon lights, there is a painting of a immature woman from the late 1800s wearing a homo's horseback riding getup, including trousers and boots. Her long hair is in a ponytail, and her face is frail and feminine. The message seems to be that it is non particularly transgressive for a adult female to wear men's garments. Information technology is just a matter of functionality.

Globe War Two fast-tracked women's adoption of men'due south clothing. When men went off to fight, women took up the piece of work they left behind, similar joining the constabulary force and becoming mechanics. Of a sudden, information technology was normal to come across women wearing men's uniforms, which included suits and jumpsuits.

All of this has paved the fashion for women of our time to choice from any role of fashion history they like. This is perhaps why women's fashion weeks around the world are a far more colorful, exciting, and creative experience, with designers mixing traditionally masculine and feminine silhouettes from dissimilar eras.

Consider the women'south autumn 2019 ready-to-wear shows at New York Mode Calendar week. The nighttime business suit was very much in vogue. Chanel, Alexander McQueen, and Balenciaga all played effectually with suits, sending women onto the rail with boxy blazers. I Rick Owens ensemble featured a blazer on top of a bodysuit and no trousers. Only other designers created highly feminine outfits. Paco Rabane sent models out in flowing floral dresses. Rodarte created frilly white gowns full of lace, also as headbands that looked like halos and shoulder pads that looked like angel'south wings.

The men'southward shows, on the other paw, were largely variations of the adjust. Alyx created a arrange out of leather. Berluti created a suit with a bronze polished outside. Alexander McQueen created a suit out of layers of houndstooth fabrics. In that location were but a couple of outliers. Palomo Espana sent a male person model out in a floral bohemian gown, and Thom Browne created long white futuristic gowns. Only these were exceptions that proved the rule: Men's fashion is more reluctant to bend gender norms.

Brief Antiestablishment Sentiment

What does it take to get men to abandon their loyalty to the suit, and become more than adventurous with their clothing? Finamore says that the last century offers a couple of clues.

In her analysis, she has observed only a few moments when men have been willing to comprehend color, patterns, and flowing silhouettes. The almost obvious example is during the 1960s and 1970s, which is sometimes known as the Peacock Revolution in menswear. Men began growing out their hair and wearing colorful, ofttimes sexualized clothes that were unlike anything men had worn over the previous century.

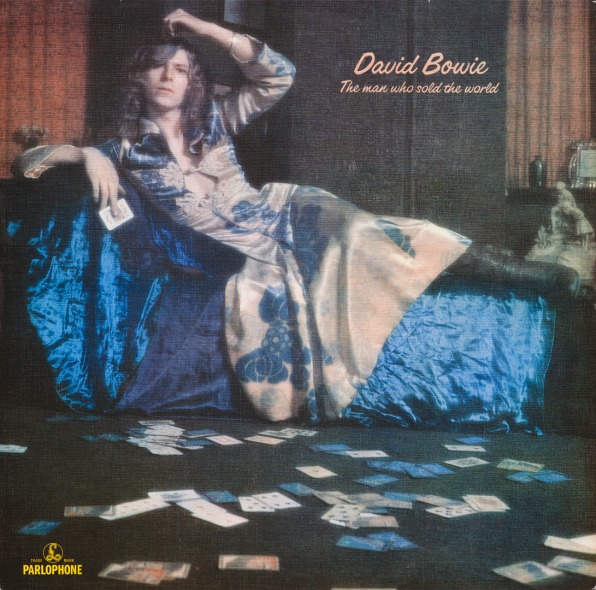

The showroom features pictures of young men wearing floral patterns and trousers with bell bottoms that added curves to an otherwise very staid garment. The near extreme version of this trend can be seen in the 1970 David Bowie album encompass forThe Human Who Sold the World,which features Bowie in a long floral apparel, boots, and long, curly hair. "Ideas well-nigh masculine clothing were challenged," says Finamore.

As Finamore tells information technology, these moments are related to larger cultural developments. During this era, the rejection of traditional masculine wear was a way for young men to express their opposition to the establishment, peculiarly suit-wearing politicians and corporate leaders. Again, the adapt was symbolic of patriarchal power, simply young men at the fourth dimension were uneasy with what their patriarchs were doing.

By the 1980s, this challenge to traditional menswear had faded abroad. In fact, Finamore sees a kind of overcorrection to these more flamboyant styles, equally menswear brands reverted to much more than traditionally masculine looks. For instance, the high-stop Italian suiting company Brioni created colorful floral suits in the 1960s and 1970s, but from the 1980s onward, Brioni suits have rarely strayed from dark colors and angular cuts.

Another Way Revolution?

Finamore proposes that we are currently in a moment when young, politically active people are pushing back against the authority, fighting for things like stricter gun laws, women's rights, and marriage equality. And yet, strangely, we're not seeing the same kind of radical rejection of traditionally masculine clothing. "We haven't seen men adopting more colorful attire on a wide calibration," she says. "We haven't seen them wearing skirts, for instance."

But we are slowly moving toward a more than gender-neutral aesthetic in culture every bit a whole. This is partly because our culture is slowly beginning to decline the accommodate, and the male power it represents. Workplaces accept become increasingly coincidental, with tech and creative industries ditching suits, chinos, and blazers. In its identify, activewear and jeans have become the norm, and in both cases, the looks are fairly like for men and women. "Today, there is nothing more androgynous than jeans and a T-shirt," says Finamore.

The future of fashion, and then, is a more than subtle blending of masculine and feminine looks. Men and women are already wearing very similar clothes, and every so oft, traditionally feminine colors and silhouettes have a way of sneaking into menswear in well-nigh ephemeral ways. Take, for instance, the work of Jordanian-Canadian designer Rad Hourani, whose work is on display in the exhibit. He describes his clothes every bit genderless, which means creating an aesthetic that doesn't expect particularly masculine or feminine. He's known for his coats, which take a flowing curtain and seem both reminiscent of a military trench glaze and a gown. It's neither hither nor there.

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/90338438/what-will-it-take-for-more-men-to-wear-skirts

0 Response to "1970 Exterior Photographs of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston"

Post a Comment